Have you ever watched a documentary or listened to a podcast and thought, “I want to dig into that case myself”? You are not alone!

True crime stories—real crimes involving real people have become hugely popular. People search for true crime information millions of times a year. Many of us are drawn in by the mystery, the psychology, and the desire to see justice served.

But here is a big truth: researching a real crime is much harder than watching a show. It requires a lot of care, respect, and hard work. It takes Expertise (knowing how to look), Experience (learning as you go), Authoritativeness (using real sources), and Trustworthiness (telling the story honestly).

This article will show you the exact steps for how to research true crime cases. We will guide you from the very beginning, helping you find clear facts and tell true stories in a way that is helpful and responsible. For more general information about true crime, start here: Plubeck Homepage.

Quick Note on Ethical and Legal Responsibilities

When you research, you are dealing with real people’s lives and pain. Always remember to be kind and respectful. We will talk more about this later, but think of it this way: your first job is to protect the victim’s memory and make sure your facts are 100% correct.

II. Understanding the Purpose of True Crime Research

Before you start digging, you need to know why you are researching. Your goal will change how you collect information.

Are you researching to write a book, article, podcast, or academic study?

- If you are writing a book or script (like for True Crime Books in Rural Minnesota), you might focus on storytelling and local history.

- If you are doing an academic study, you must focus on official documents and data.

- If you are creating a podcast, you might focus on finding people to interview.

Difference Between Reporting, Storytelling, and Investigative Research

| Type of Research | Main Goal | What You Need to Do |

| Reporting | To share what happened (Journalism) | Find confirmed, official facts and quote people directly. |

| Storytelling | To create an interesting narrative (Books/Podcasts) | Gather details, feelings, and timelines. You must still base it on facts! |

| Investigative | To find new clues or errors (Citizen Detective) | Look for gaps in the official story and cross-reference every small detail. |

Export to Sheets

Setting Clear Boundaries and Objectives

Do not try to solve every part of a 20-year-old case on Day 1. Start small. For example, your first objective might be: “Find the police report from the first 24 hours of the case.”

III. Start With the Basics: Case Overview

Every good research project starts with a foundation a simple understanding of the who, what, where, when, and why.

How to Define the Scope of a Case

The scope is the boundary of your project. Are you focusing on the crime itself, the trial, or the long-term effects on the community?

- Narrow Scope: Focus only on one event, like “The jury’s decision in the 1995 trial.”

- Broad Scope: Focus on a large topic, like “Historical patterns of crime in Redwood County” (which you can read about here: Historical Murders Redwood County).

Identifying Key Elements: Victim, Suspect, Timeline, Location

Ask these basic questions and write down the answers:

- Victim: Who was hurt? What was their background?

- Suspect (or Person of Interest): Who did the police look at? Were they arrested or charged?

- Timeline: When did the crime happen? When was it discovered?

- Location: Where exactly did it happen? (Use mapping tools later, like Google Street View, to get a feel for the place.)

Building an Initial Case Summary or Timeline

Start with a single document. List everything you know in a simple, bulleted list. Next, put those points in order by date. This will be your working timeline. It will change often, but it helps you see the story clearly.

IV. Gathering Reliable Primary Sources

Primary sources are the best kind. They are the original documents created at the time of the crime or trial. Think of them as the words of the people who were actually there.

A. Police Reports & Case Files

These are the most important documents you can find.

How to request documents through FOIA (Freedom of Information Act)

In the United States, you can use the FOIA (or similar state laws) to ask the government for public records.

- Identify the Agency: Figure out which police department, sheriff’s office, or state agency holds the records.

- Write a Simple Letter: State clearly that you are making a request under the state’s Public Records Law or FOIA.

- Be Specific: Give the case name, date, and location. Do not ask for “everything.” Ask for specific things like “The Initial Incident Report” or “The list of evidence.”

- Expect Delays: Getting records takes time, sometimes weeks or months.

State-by-state variations for public records

Public records laws are different everywhere. In some states, many crime documents are public after a case is closed. In other states, police reports are kept secret unless they are very old. Always search for the public records law in the state where the crime took place.

What information is typically available

- The initial report filed by the officer who first responded.

- The final report once the investigation is closed.

- Lists of evidence (but often not photos or sensitive details).

B. Court Records

Court records show what happened after a person was charged with a crime.

Accessing court dockets, indictments, motions, and transcripts

- Court Docket: This is the schedule. It lists every action taken in the case, like “Defense filed a motion on March 15th.”

- Indictment: The formal paper that says the person is charged with a crime.

- Motions: Requests made by lawyers (like asking to keep certain evidence out of the trial).

- Transcripts: The word-for-word record of what was said during the trial.

You can often find dockets and motions by visiting the courthouse in person or using online databases run by the county or state.

How to interpret legal documents

Legal language is hard! If you see words you do not know, look them up. Focus on finding the facts: the date, the specific charge, and the ruling (what the judge decided).

C. Autopsy & Medical Examiner Reports

These documents tell you exactly how the victim died.

What’s public vs. private

Generally, the full autopsy report contains private, graphic details and is not public. However, the Death Certificate and a summary of the medical examiner’s findings might be public record, especially in older, closed cases.

How to obtain them and how to read them

You need to request these from the county or state medical examiner’s office. To read them, look for the official “Cause of Death” (the reason they died) and the “Manner of Death” (such as homicide, suicide, or accident). Knowing what a medical examiner does at a crime scene helps understand these reports: What Does a Medical Examiner Do at a Crime Scene?.

V. Secondary Sources: Supplementing Your Research

Secondary sources are items like news articles, books, and documentaries. They are helpful for context, but they are not the same as a primary source.

A. News Articles & Archives

Old news reports give you a real-time snapshot of the public mood and what the police were saying that day.

Evaluating credibility of news sources

Always ask: Is this source trustworthy? A major newspaper is generally more trustworthy than a small blog. Look for articles that quote official sources like police or court records.

Using newspaper databases and local archives

Use tools like Newspapers.com or visit the local library in the town where the crime happened. Libraries often have old, physical copies or microfilms of newspapers that are not online. When researching historical cases, local archives are key for things like Yellow Medicine County Crime History Book.

B. Books, Documentaries, and Academic Journals

These sources provide big-picture ideas and analysis.

How to extract data without relying on narrative bias

Writers want to tell a good story. This can lead to bias (favoring one side). If a book claims something, always try to find the primary source (police report or court record) that supports it. Do not just trust the story; trust the facts the story is built upon.

Cross-checking published interpretations

If three different books agree on a key fact, it is probably true. If they disagree, you have found a gap in the research that you need to fill with primary sources.

C. Online Communities (Use With Caution)

Sites like Reddit or Websleuths are places where people discuss cases.

Pros and cons

- Pro: You can find great ideas, new perspectives, and often helpful links to old news articles.

- Con: These sites are full of speculation (guesses) and sometimes completely wrong information. Never treat an online theory as a fact.

How to verify claims from online discussions

If someone online says, “The killer owned a red truck,” your job is to find the police report that mentions the red truck. If you cannot find a primary source, the claim must be left out of your final project.

VI. Interviewing People Connected to the Case

Talking to people is a huge part of true crime research, but it must be done with extreme sensitivity.

How to respectfully approach victims, families, law enforcement, lawyers

- Be Kind and Honest: State clearly who you are and why you are contacting them.

- Ask Before You Go: Never surprise someone. Send a respectful letter or email first.

- Respect “No”: If a family member says they do not want to talk, you must accept their decision immediately. You should focus on respecting trauma and avoiding When Good Intentions Fail.

Preparing questions

Write down your questions ahead of time. Start with open-ended questions that let them tell their story (“Can you tell me about the day you found out?”) instead of questions that force a “yes” or “no” answer.

Recording and documenting properly

Always ask permission before recording audio or video. If you cannot record, take detailed notes immediately after the interview. Make sure your notes capture the speaker’s exact words when possible.

Ethical boundaries and respecting trauma

Your research should never cause new harm. If someone becomes upset, stop the interview. Remember that you are writing about the worst day of their life.

VII. Organizing Your Research

Good research is not just about finding facts; it is about keeping track of them.

A. Creating a Case Folder System

Treat your research like a detective’s case file.

- Digital Folders: Create clear folders on your computer: 1. Primary Sources, 2. News Articles, 3. Interviews, 4. Timelines.

- Spreadsheets: Use a simple spreadsheet to log every document. Include columns for: Source Type (e.g., Police), Date of Document, Key Fact, and File Name/Link. This helps you organize details about things like missing people: Famous People Who Went Missing and Were Never Found.

B. Building a Case Timeline

This is the most important document you will create.

Chronological mapping

List every event in order, from the earliest to the latest.

- Example: 1/1/1990: Victim last seen at 9:00 PM. (Source: Witness statement)

- Example: 1/2/1990: Police file initial report at 7:00 AM. (Source: Police Report)

Identifying inconsistencies and gaps

If the police report says the body was found at 7:00 AM, but a news article says 9:00 AM, that is an inconsistency. You need to figure out which source is right. Gaps are the parts of the timeline where you have no information.

C. Cross-Referencing Facts

This means checking every piece of information against another piece. Does the witness statement match the evidence log? Does the suspect’s alibi (what they claim they were doing) line up with public records?

VIII. Advanced Investigation Techniques

Once you have the basics, you can start digging deeper.

A. Public Records Searches

Look beyond the crime itself to understand the people involved.

- Property Records: Can show who owned the land or house.

- Marriage/Divorce Records: Can show relationships or motives.

- Prison Records: Can show a suspect’s past.

- Business Filings: Can show financial problems or partnerships.

B. Analyzing Evidence Patterns

This is where you look for connections in the crime.

- Behavioral patterns: Did the suspect act the same way in previous incidents?

- Crime scene indicators: What does the location tell you about the crime?

- Offender profiling basics: You are not a profiler, but understanding the basics can help you see if a published profile matches the facts.

C. Geographical Tools

Maps are your friends!

- Google Maps & Street View: Use these to see what a location looks like now and try to find old photos to see what it looked like then. This helps you understand distances and witness viewpoints.

- Geotagging social media posts: If the case is recent, you might be able to find old posts tied to a location, but these are often protected by privacy rules.

- Crime mapping tools: Some cities offer maps that show crime hotspots.

IX. Legal Considerations

You must be careful about what you write and publish. The law protects people, even criminals.

What information you can legally publish

In general, you can publish anything that is part of the public record (like court transcripts). However, even public information can cause problems if you use it incorrectly.

Privacy laws and defamation risks

- Defamation: This means damaging someone’s reputation by making a false statement. If you state a rumor as a fact, you can be sued. Always use words like “allegedly,” “was accused of,” or “according to the court record.”

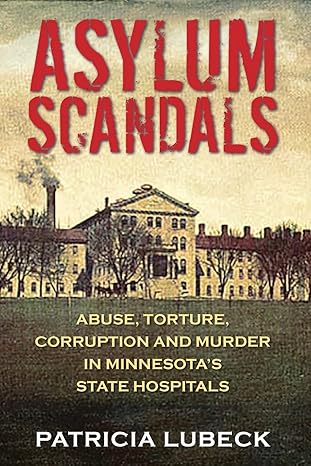

- Limitations: You cannot discuss sealed records (records the court closed to the public) or details about minors without a lot of legal trouble. Be extra careful when discussing issues involving legal and ethical missteps, like those covered here: Unintentional Legal and Ethical Lapses Asylum Scandals.

X. Ethical Responsibilities

This is the heart of responsible true crime research.

Avoid sensationalism

Sensationalism means making the story bigger, scarier, or more shocking than it really was, just to get attention. Focus on the facts and the impact, not the shocking details.

Respect for victims

The victim is not a plot device. Their story is the most important part. Always refer to them with dignity.

Handling graphic details

Do you need to describe gruesome details to tell the story? Usually, the answer is no. State the fact (e.g., “The cause of death was confirmed by the medical examiner”) without including the gory specifics. When dealing with difficult topics, such as those related to past institutional abuse, respect and careful language are vital, especially when discussing Controversies in Psychiatric History.

Understanding the real-world impact of true crime content

Your work can influence a real investigation. It can also hurt a family. The goal is to bring attention and justice, not simply to entertain. Sometimes, even when people try to do good, their actions have negative results. Read more about this challenge here: Inside the Asylum.

Ethical storytelling guidelines

- Victim-Centered: Keep the victim’s life and voice central.

- Fact-Driven: Only publish what you can prove with a primary source.

- Transparency: Be open about what you know and what you do not know.

XI. How to Verify and Fact-Check

This step is what turns a hobbyist into an expert.

A. Source Validation Checklist

Check every fact against this list:

- Who created the information? (Police? Witness? Newspaper?)

- Is it a direct witness or a third-party account? (A neighbor is a direct witness; a local historian is a third party.)

- Can another, separate source confirm it? (If the police report and the court transcript say the same thing, it is strong.)

B. Spotting Misinformation

Misinformation is false or inaccurate information.

- Red flags: Stories with no sources, overly emotional language, or facts that seem too perfect.

- Differentiating speculation vs. confirmed evidence: Use words that show the reader the difference.

- Confirmed Evidence: “The search warrant, dated May 1, showed…”

- Speculation: “Many online users believe that…”

C. Building a “Fact-Only” Document

Create a master sheet that contains only the facts you have confirmed with at least one primary source. This document is the bedrock of your article or book.

XII. Presenting Your Findings

How you share your research is just as important as the research itself.

A. For Writers (Books/Blogs)

How to structure case narratives

Start with the known facts. Move to the investigation. End with the legal result or the mystery that remains.

How to avoid libel

To avoid getting sued (libel), never state an opinion as fact. Never say: “The neighbor murdered him.” Say: “The neighbor was arrested and charged with the murder, according to court documents.”

B. For Podcasters & Content Creators

Ethical publishing

Always include a brief statement at the beginning of your content that respects the victim and thanks the sources.

Citing sources on episodes

Even if you do not read the full source list on the air, include a link to your source notes in the description of the episode. This proves your trustworthiness.

C. For Academic or Investigative Reports

Proper citation styles

Use formal citation styles (like Chicago or MLA) to show exactly where you got every piece of information.

Research transparency

Publish your methods. Explain how you looked for documents and who you interviewed.

XIII. Tools & Resources

Good researchers use good tools.

| Resource Type | What it helps you do | Examples (General) |

| FOIA Request Tools | Helps you find the right government office and forms. | State-specific government websites |

| Newspaper Databases | Gets you access to old, archived articles. | Newspapers.com, Chronicling America |

| Court Record Platforms | Lets you search for dockets and documents online. | Court websites (e.g., PACER for Federal cases) |

| Interview Templates | Provides scripts and question guides for talking to people. | Your own customized document |

| Research Spreadsheets | Helps you track every fact and source. | Google Sheets, Airtable |

Export to Sheets

XIV. Conclusion

Learning how to research true crime cases is a commitment. It requires respect for the thousands of cases that remain unsolved—experts estimate that nearly 340,000 cases of homicide and non-negligent manslaughter went unsolved between 1965 and 2021. This staggering number shows why careful, ethical research is so important.

Your work, when done responsibly, can educate the public, honor victims, and sometimes even help shed new light on a cold case. Always prioritize accuracy over entertainment. Be thorough, be kind, and remember the responsibility you hold when telling someone’s real-life story.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is it okay to research a case that is still “active” or “open”?

A: You can research open cases, but you must be very careful. Police will not give you primary sources. You must rely on court-approved public documents and news reports. Never interfere with an active investigation or share information that might compromise law enforcement efforts.

Q: How do I know if a source is primary or secondary?

A: A primary source is created by someone who was there or made the official record. (Example: The police officer who wrote the report.) A secondary source talks about the primary source. (Example: A journalist writing about the police report.) Always aim for primary.

A: You can use social media posts, but they must be treated as unverified statements. Never state a social media post as a fact unless you can confirm it with an official source (like a police report confirming a missing person’s last location based on a photo).

Q: What should I do if my research uncovers a new piece of evidence for a cold case?

A: Do not publish it immediately. You should contact the local police department or law enforcement agency handling the case and provide them with the information directly. Let the police use the information in the proper legal way.

Q: What if a case is very old and the documents are gone?

A: For very old cases, you must rely more heavily on local historical societies, university archives, and old newspaper microfilms. Look for county history books and public records that might mention the crime.

This video helps put the scale of the challenge into perspective by discussing the total number of unsolved murder cases across the United States. How Many Murder Cases Go Unsolved?

How Many Murder Cases Go Unsolved? – CountyOffice.org – YouTube

0 Comments